Finance Bill 2024 Long Con: What Really Happened After the Protests

On June 22, 2025, Majority Leader Kimani Ichung’wah confirmed this sequence. He told worshippers: “On December 4, 2024, only five months later, everything that was in the finance bill was passed quietly…until 97 per cent of it passed”. This admission sparked a viral narrative that nearly the entire Finance Bill 2024 “sneaked through” Parliament after the protests. Ichung’wah argued the government held off on the taxes to let public anger subside, then implemented them via separate bills. He insisted Kenyans had been misled about the worst provisions (e.g. the high-value taxes were actually on imports only).

Kimani Ichungwa’s assertion that 97% of the punitive proposals from the 2024 Finance Bill were passed through “secret bills” is best understood as a politically charged oversimplification rather than a precise factual statement, yet it contains a significant kernel of truth in its underlying spirit. A direct, clause-by-clause re-enactment of 97% of the exact punitive proposals did not occur. Crucially, several highly contentious and broadly impactful items that directly affected the daily cost of living for most citizens (such as the 16% VAT on bread, the motor vehicle tax, and KRA’s unrestricted access to taxpayer data) were indeed genuinely dropped from the legislative agenda following the widespread protests.

Background: The Finance Bill 2024 and Public Uproar

The Finance Bill 2024 was introduced in May 2024 with the ambitious goal of raising KSh 346 billion to address Kenya’s national debt and fund development projects. This fiscal imperative was significantly influenced by conditions set by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which had been pushing the Kenyan government to implement austerity measures and increase its tax-to-GDP ratio from 13.5% to an ambitious 20% by 2027.

The bill, however, quickly became a flashpoint for public discontent due to its numerous controversial proposals. These included a 16% Value Added Tax (VAT) on essential goods like bread, a new annual 2.5% tax on motor vehicles, increased excise duties on mobile money transfers, and the introduction of an “Eco Levy” on various products including diapers and mobile phones. A particularly alarming proposal was the amendment to the Kenya Data Protection Act, 2019, which would have granted the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) unrestricted access to taxpayers’ financial data, such as mobile money statements, without requiring court orders. These measures were perceived by many as disproportionately burdening poor and middle-class Kenyans already struggling with the cost of living.

The public’s response was swift and unprecedented. The #RejectFinanceBill2024 protests, primarily mobilized by young Kenyans (Gen Z) through social media platforms like X and TikTok, quickly escalated beyond Nairobi to cities nationwide. These demonstrations were characterized by their scale and intensity, leading to tragic confrontations with security forces. At least 65 protestors were killed and hundreds more wounded and traumatized by the use of live ammunition and crowd-control weapons. Reports also emerged of activists being abducted and unlawfully arrested, further fueling public anger. The protests culminated in the storming of the Parliament building on June 25, 2024, a dramatic display of public frustration.

In response to the overwhelming public pressure and the escalating violence, the government initially announced some concessions on June 18, 2024. Specific provisions, such as the 16% VAT on bread, the motor vehicle tax, the 25% excise duty on vegetable oil, and the increase in mobile money transfer taxes, were scrapped. The controversial “Eco Levy” was curtailed to apply only to imported products, and the proposed KRA access to taxpayer data was suspended. However, these partial withdrawals failed to satisfy the protestors, who demanded the abandonment of the

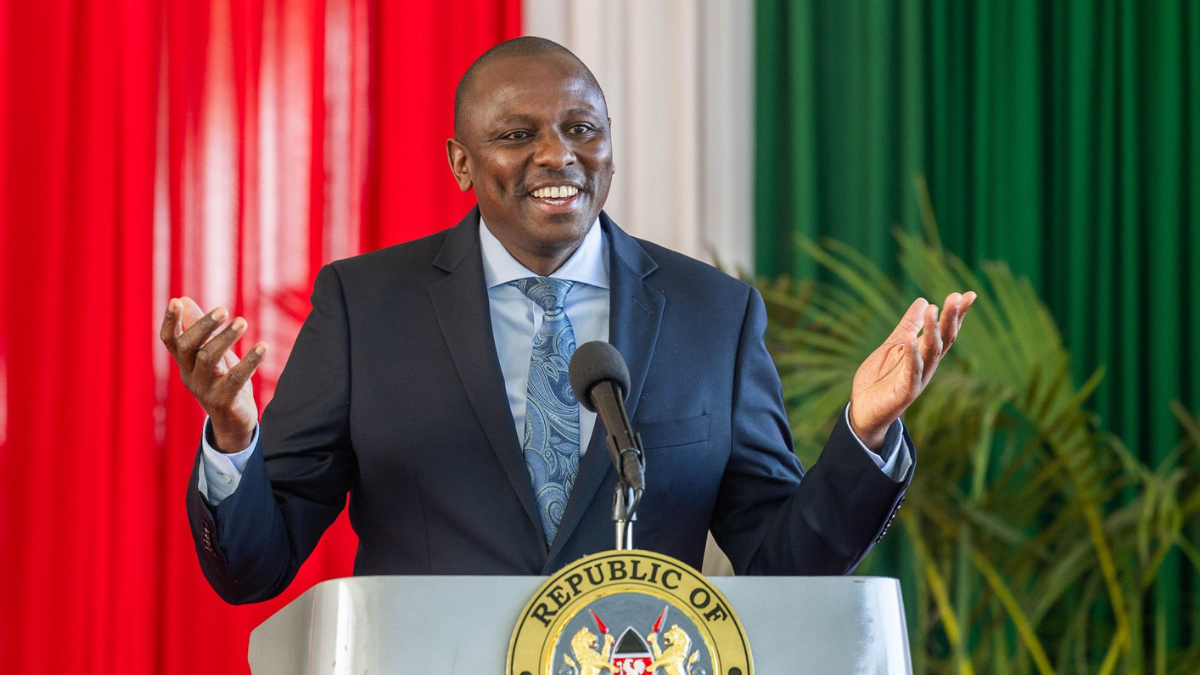

entire bill. Ultimately, President William Ruto declined to sign the Finance Bill 2024 into law on June 26, 2024, and officially rejected it on June 28, acknowledging that the Kenyan people “want nothing” to do with it. This rejection was accompanied by an order for a significant KSh 999 billion budget cut to offset the anticipated revenue shortfall.

The immediate impact of the public’s opposition was undeniable. The government, faced with unprecedented civil unrest and a direct challenge to its fiscal agenda, was compelled to withdraw a major piece of legislation. This outcome demonstrated the potent influence of robust citizen mobilization, particularly youth-led movements, in shaping immediate policy outcomes. It also set a significant precedent for how future Kenyan governments might respond to widespread public dissent concerning fiscal policy. The forceful rejection, despite the acknowledged fiscal need, signaled a strong societal resistance to austerity measures that place the majority of the financial burden on ordinary citizens. This outcome necessitated that the government actively explore and implement alternative, less regressive revenue generation strategies or risk perpetuating social unrest.

The Legislative Recourse: Examining the “Secret Bills”

Following the high-profile rejection of the consolidated Finance Bill 2024, the Kenyan government introduced a series of other legislative instruments towards the end of 2024. These included the Tax Laws (Amendment) Act 2024, the Business Laws (Amendment) Act 2024, and the Tax Procedures (Amendment) Act 2024. These acts were formally assented to by the President on December 11, 2024, and subsequently became effective on December 27, 2024. Kimani Ichungwa’s statement explicitly linked these two amendment bills (Tax Laws and Business Laws) to the “quiet” passage of the original Finance Bill’s provisions on December 4, 2024. He noted that the government paused the bill in June to “let tempers cool,” then re-introduced its provisions “quietly, without any deaths or throwing stones”.

This approach of dispersing new or modified tax measures across multiple, less prominent amendment acts, rather than reintroducing a single, consolidated Finance Bill, inherently makes it more challenging for the general public and even civil society organizations to track the full scope of fiscal changes. This fragmentation can be interpreted as a deliberate attempt to dilute public scrutiny and circumvent the concentrated opposition that a singular, comprehensive tax bill would likely attract, effectively shifting the burden of monitoring and understanding complex legislative changes from the government to the public.

Analysis of Key Provisions

A detailed examination of the subsequent legislative acts reveals a complex interplay of reintroductions, modifications, and new measures:

Tax Laws (Amendment) Act 2024 (TLAA 2024)

This Act introduced a wide array of tax proposals aimed at amending existing statutes like the Income Tax Act, VAT Act, and Excise Duty Act. Key provisions include:

- Digital Service Tax (DST) replaced with Significant Economic Presence (SEP) tax: While the original Finance Bill 2024 proposed a 1.5% DST and a 6% SEP tax , the TLAA 2024 repealed the DST and instead introduced a 3% SEP tax on non-residents providing digital services. This represents a modification and reintroduction of a tax on digital services, albeit with a new rate and structure.

- Introduction of a 15% Minimum Top-Up Tax (MTT) for multinationals: This measure aligns with the OECD’s Pillar Two framework, ensuring a minimum 15% effective tax rate for multinational groups with consolidated annual turnover exceeding EUR 750 million.

- Expanded allowable deductions for pension and mortgage contributions: The Act significantly increased tax-deductible contribution limits for registered pension and provident funds from KES 240,000 to KES 360,000 annually, and raised the deductible mortgage interest to KES 360,000 per year.

- Exemptions on pension scheme withdrawals: Introduced tax exemptions for income derived from registered retirement benefit schemes for individuals who have reached retirement age or withdraw due to ill health.

- Expanded tax-exempt non-cash benefits and meal allowances: Increased monthly limits for non-cash employment benefits and meal allowances to KES 5,000 each.

- Expanded definition of “royalty”: Included software usage as royalty, thereby subjecting software purchases to withholding tax.

- Introduced Withholding Tax (WHT) on the sale of scrap: At a rate of 1.5%.

- Allowed deduction for Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) and Affordable Housing Act contributions: This measure aims to alleviate the financial burden on employees.

- Detailed VAT and Excise Duty Amendments:

- VAT: Reclassified “Transfer of a Business as a Going Concern (TOGC)” from standard-rated to exempt. Shifted several items from zero-rated to exempt (e.g., inputs for agricultural pest control products, fertilizers), which could increase costs for manufacturers and farmers. Moved some items from exempt to standard-rated (e.g., entry fees into national parks, services of tour operators, betting/gaming/lotteries services, hiring/leasing/chartering of aircrafts). Made all goods of Chapter 88 (Aircraft, spacecraft, and parts thereof, excluding helicopters) exempt.

- Excise Duty: Introduced excise duty for services provided by non-residents through digital platforms. Revised excise duties on imported sugar, cigarettes, nicotine products, alcoholic beverages (now based on pure alcohol content), imported plastic plates, imported electric transformers, printing ink, ceramic sanitary fixtures, float glass, ceramic tiles, and coal. Significantly increased excise duty on telephone and internet data services (from 15% to 20%), money transfer services by banks and cellular providers (from 15% to 20%), and betting/gaming/lottery/prize competition services (from 12.5% to 15%). Crucially, it also introduced a new 20% excise duty on fees charged for advertisement via the internet and social media. These represent direct reintroductions of increased taxes on services that were highly contentious in the original Finance Bill.

Tax Procedures (Amendment) Act 2024

This Act focused on amendments relating to tax processes and administration. Key provisions include:

- Extended tax amnesty: Extended the amnesty on interest, penalties, and fines to June 30, 2025, for tax debt accrued up to December 31, 2022.

- Amended computation of time for appeals: Excluded Saturdays, Sundays, and public holidays when computing time for appeals to tax appeals tribunals and courts.

Business Laws (Amendment) Act 2024

This Act introduced a broad range of legislative changes aimed at enhancing the regulatory framework of various bodies, effective December 27, 2024. Key provisions include:

- Banking Sector Reforms: Increased penalties for non-compliance by financial institutions and credit reference bureaus. Progressively increased core capital requirements for banks and mortgage finance companies.

- Expanded Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) Regulatory Mandate: Broadened CBK’s oversight to include all non-deposit-taking credit providers, such as buy now pay later services, peer-to-peer lending, and asset financing. It also transferred the regulation of non-deposit-taking microfinance businesses to CBK.

- Other Business-Related Amendments: Amended the Investment Promotion Act, Standards Act, Anti-Counterfeit Act, and Kenya Industrial Research and Development Institute Act to promote local manufacturing, enhance product compliance, and streamline intellectual property rights. Notably, it also reduced excise duty on packaging and non-virgin test liners to avoid double taxation.

The perceived “secret” nature of these bills, as implied by Ichungwa’s comment about them passing “quietly,” points to a significant issue with public participation. While the Business Laws (Amendment) Bill 2024 did undergo formal public participation, with invitations extended to stakeholders and public hearings held in various counties , the overall public perception, as captured by Ichungwa’s statement and the user’s query, suggests that this participation was either insufficient, poorly publicized, or that the public’s input was not perceived as genuinely influential. The government’s proactive decision to launch a

new online portal for public views on the Finance Bill 2025, explicitly stating its aim to “enhance transparency and public engagement” and “avoid the public outcry experienced during the Finance Bill 2024” , serves as an implicit acknowledgment that prior public participation mechanisms (including for the December 2024 amendment bills) were indeed flawed or perceived as inadequate by the public. This situation highlights a deeper systemic issue beyond merely the content of the bills: the

integrity and perceived legitimacy of the legislative process itself. Even if formal public participation sessions occurred, if they do not lead to demonstrable responsiveness or if the public feels blindsided by the eventual legislation, the entire process’s credibility is undermined.

Verifying the 97% Claim: A Comparative Analysis

Kimani Ichungwa’s assertion that “97% of the punitive proposals” made it through parliament via “secret bills” requires careful scrutiny. This figure is unlikely to be a literal, clause-by-clause percentage, given the significant items that were genuinely dropped from the original Finance Bill 2024. Instead, it functions as a rhetorical device primarily intended to assert the government’s ultimate success in achieving its broader fiscal objectives despite the public outcry.

Proposals Explicitly Dropped and Not Reintroduced

Several highly contentious proposals that directly impacted the daily cost of living for the majority of citizens were indeed abandoned following the protests:

- 16% VAT on bread, cooking oil, eggs, and other staples: This was a major point of contention and appears to have been genuinely abandoned.

- Motor vehicle tax: This annual tax, which would have impacted vehicle owners, was also removed.

- Eco-levies on locally manufactured diapers and phones: While the original Eco Levy was curtailed to only affect imported products in the Finance Bill 2024, the December package explicitly abandoned it for locally manufactured items.

- KRA access to taxpayers’ data without court orders: This highly controversial provision, impacting privacy, was suspended.

- 25% excise duty on vegetable oil: This tax, which would have significantly increased the price of soap, was dropped.

- Increase of the Road Maintenance Levy from KES 18 to KES 25 per litre of fuel: While not explicitly listed as dropped by Ichungwa, this measure was not found to be reintroduced in the detailed summaries of the subsequent acts.

These withdrawals indicate a genuine, albeit limited, concession to public pressure, particularly on the most visible and broadly impactful taxes.

Proposals Modified or Reintroduced

Despite the abandonment of some key proposals, a significant number of other tax-increasing measures, particularly those targeting digital services, financial transactions, and specific imported goods, were either reintroduced with modifications or new, similar taxes were introduced:

- Digital Service Tax (DST) / Significant Economic Presence (SEP) Tax: The original Finance Bill 2024 proposed a 1.5% DST and a 6% SEP tax. The Tax Laws (Amendment) Act 2024, however, repealed the DST and introduced a 3% SEP tax on non-residents providing digital services. This is a clear reintroduction of a tax on digital platforms, albeit with a modified rate and structure.

- VAT on Electric Vehicles/Bikes/Solar Batteries: The Finance Bill 2024 proposed VAT on these items. While the VAT status of these specific items isn’t explicitly detailed as reintroduced in the same form, the TLAA 2024 did introduce new excise duty exemptions for locally assembled electrical vehicles , indicating a continued focus on this sector with nuanced tax adjustments.

- Excise Duty on Financial Services, Internet, Betting/Gaming/Advertisements: The Finance Bill 2024 proposed increases on these services. The TLAA 2024 significantly increased excise duty on telephone and internet data services (from 15% to 20%), money transfer services (from 15% to 20%), and betting/gaming/lottery/prize competition services (from 12.5% to 15%). Crucially, it also introduced a new 20% excise duty on fees charged for advertisement via the internet and social media. These represent direct reintroductions of increased taxes on services that were highly contentious in the original Finance Bill.

- Minimum Top-Up Tax: Proposed in the Finance Bill 2024 , this tax on multinational groups was reintroduced in the TLAA 2024.

- Withholding Tax on goods supplied to public entities: This was proposed in the Finance Bill 2024 and subsequently reintroduced in the TLAA 2024.

- Withholding Tax on interest from infrastructure bonds: Proposed in the Finance Bill 2024 and reintroduced in the TLAA 2024.

- Withholding Tax on sale in digital marketplaces: Proposed in the Finance Bill 2024 and reintroduced in the TLAA 2024.

New Proposals Introduced in Subsequent Acts

Beyond the reintroduction or modification of previous proposals, the subsequent acts also introduced a range of entirely new measures that were not explicitly part of the original Finance Bill 2024’s public debate:

- Increased allowable pension and mortgage contributions.

- Exemptions on pension scheme withdrawals.

- Allowed deduction for Social Health Insurance Fund and Affordable Housing Act contributions.

- Expanded tax-exempt non-cash benefits and meal allowances.

- Expanded royalty definition to include software.

- New WHT on sale of scrap.

- Various VAT reclassifications (e.g., Transfer of a Business as a Going Concern from standard-rated to exempt, agricultural inputs from zero-rated to exempt, national park fees from exempt to standard-rated).

- New excise duties on a range of imported goods including electric transformers, printing ink, ceramic sanitary fixtures, float glass, ceramic tiles, coal, saturated polyester, vinyl acetate/vinyl esters, and emulsion-styrene acrylic.

- Significant changes to the Banking Act, CBK Act, and other business-related laws, focusing on penalties, capital requirements, and regulatory oversight of non-deposit-taking credit providers.

The initial rejection of the Finance Bill 2024 was undoubtedly a political victory for the public. However, the subsequent passage of other legislative instruments containing similar or modified tax proposals reveals a critical distinction: the rejection of a specific bill does not automatically equate to the abandonment of the government’s underlying fiscal policy objectives. The government’s commitment to increasing revenue and adhering to IMF conditions remained steadfast. This dynamic underscores the complex reality of legislative processes. While significant public pressure can force a retreat on a highly visible legislative instrument, the broader policy agenda, particularly concerning national fiscal targets, can be pursued through alternative, less conspicuous means. This challenges the simplistic notion of a complete public “win” and emphasizes the need for sustained vigilance and understanding of the entire legislative ecosystem.

The government demonstrably dropped the most highly visible and broadly impactful taxes (e.g., VAT on bread, motor vehicle tax, local eco-levies) that directly affected the majority of citizens and were the primary catalysts for the widespread protests. Concurrently, it reintroduced or increased taxes on digital services, financial transactions, and specific imported goods. While still impactful, these latter taxes might affect a more specific segment of the population or be less immediately noticeable than taxes on basic necessities. The introduction of a minimum top-up tax for multinationals also strategically shifts some of the revenue burden to large corporations. This pattern suggests a deliberate strategic recalibration by the government: sacrificing some broadly unpopular taxes in favor of others that could still generate significant revenue but provoke less widespread, immediate public backlash. It represents a sophisticated political maneuver to achieve fiscal goals while attempting to manage public discontent, indicating a learning curve for the government in navigating public sentiment on taxation.

Kimani Ichungwa’s assertion of “97% passage” is highly unlikely to be a literal, clause-by-clause percentage, given the significant items that were genuinely dropped. Instead, it functions as a rhetorical device primarily intended to assert the government’s ultimate success in achieving its broader fiscal objectives despite the public outcry. It serves as a political statement aimed at reinforcing the government’s resolve and, perhaps, subtly mocking the perceived efficacy of the protests. This highlights the inherently political nature of public discourse surrounding legislative actions. Figures and claims, even if not strictly accurate in a technical or quantitative sense, are frequently employed to shape narratives, influence public perception, and communicate political messages.

Implications for Governance and Public Trust

The events surrounding Kenya’s Finance Bill 2024 and the subsequent legislative actions carry significant implications for the nation’s governance and the delicate balance of public trust.

The evidence strongly suggests that while the government did make significant, visible concessions by withdrawing the highly contentious Finance Bill 2024 and dropping some of its most unpopular provisions, it simultaneously pursued many of its core revenue-generating objectives through other, less consolidated legislative channels (Tax Laws, Business Laws, Tax Procedures Amendment Acts) later in the year. This dual approach, characterized by a public retreat followed by a quiet re-implementation of similar measures, lends substantial credence to the “political dance” narrative. The initial rejection served as a crucial mechanism to diffuse immediate public anger and halt widespread violence, while the subsequent, less publicized passage of related measures allowed the government to recover a significant portion of its desired revenue. The “97% figure,” while likely an overstatement in terms of

identical proposals, effectively captures the government’s perceived success in achieving its overall fiscal aims despite initial public opposition.

The strategic use of multiple, less prominent amendment bills after the high-profile rejection of the main Finance Bill raises serious questions about government transparency and the integrity of public participation. Even though some of these subsequent bills did undergo formal public participation , the fragmented approach and the widespread perception of “secret” passage indicate a significant deficit in effective and

perceived transparent engagement. The government’s proactive move to introduce an online portal for public views on the Finance Bill 2025, explicitly stating its aim to “enhance transparency and public engagement” and “avoid the public outcry experienced during the Finance Bill 2024” , serves as a tacit, yet powerful, admission that the previous processes (including for the December 2024 amendments) were either inadequate or failed to build public trust. The very existence of a Public Participation Bill 2024 underscores an official recognition of the need for structured guidelines for citizen engagement. However, its development and timing, occurring in the aftermath of the 2024 protests, strongly suggest it is a reactive measure rather than a pre-existing preventative framework for public outcry.

The rejection of the Finance Bill 2024 had an immediate and measurable fiscal impact. The Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) missed its revenue target by KSh 163 billion in the first half of the Financial Year 2024-2025, with the rejection of the bill explicitly cited as a contributing factor. The Treasury had initially projected to raise KSh 346 billion from the original bill by June 2025, and the period of non-implementation between June and December 2024 alone resulted in an estimated loss of KSh 160 billion in revenue. However, Ichungwa’s claim that the December amendments (Tax Laws and Business Laws) had already netted KSh 187 billion in extra tax by May 2025 indicates that the subsequent legislative measures were indeed successful in recovering a significant portion of the initially foregone revenue. This highlights the government’s persistent and strategic drive to increase the tax-to-GDP ratio, a long-term fiscal objective.

The observed sequence of events—massive public protests leading to the rejection of a major bill, followed by the quiet passage of similar measures through fragmented legislative instruments, and then the government’s subsequent efforts to improve public participation for future bills—reveals a dynamic, adaptive cycle in governance. While public pressure can effectively halt specific legislative instruments, it may not fundamentally alter the government’s underlying fiscal objectives, especially when these objectives are driven by external pressures like IMF conditions. This pattern suggests an ongoing tension between direct democratic accountability (as expressed through protests) and technocratic imperatives (fiscal stability, debt management). It implies that governments, when faced with overwhelming public opposition, may resort to more circuitous legislative paths to achieve their goals, necessitating continuous public vigilance and adaptation in advocacy strategies.

The “political dance” narrative, reinforced by statements like Ichungwa’s and the perceived circumvention of public will, inevitably leads to deep-seated public distrust. This distrust can manifest in various forms, including reduced voluntary tax compliance (as citizens feel their contributions are extracted unfairly or through deceptive means) or further social unrest. The government’s proactive efforts to enhance public participation for the Finance Bill 2025 are a direct, albeit belated, response to this erosion of public trust. Persistent public distrust can have significant long-term consequences, undermining governance stability, hindering the effectiveness of economic policies, and fracturing the social contract between the state and its citizens. It compels the government to expend more resources on managing public relations and less on actual development, potentially creating a self-perpetuating cycle of discontent and fiscal challenges.

Conclusion: Truths, Lies, and the Path Forward

Kimani Ichungwa’s assertion that 97% of the punitive proposals from the 2024 Finance Bill were passed through “secret bills” is best understood as a politically charged oversimplification rather than a precise factual statement, yet it contains a significant kernel of truth in its underlying spirit. A direct, clause-by-clause re-enactment of 97% of the exact punitive proposals did not occur. Crucially, several highly contentious and broadly impactful items that directly affected the daily cost of living for most citizens (such as the 16% VAT on bread, the motor vehicle tax, and KRA’s unrestricted access to taxpayer data) were indeed genuinely dropped from the legislative agenda following the widespread protests.

Despite these specific withdrawals, a substantial portion of the revenue-generating intent and other specific tax increases from the original Finance Bill 2024 were indeed enacted through the Tax Laws (Amendment) Act 2024 and the Business Laws (Amendment) Act 2024 in December 2024. These included modified digital service/SEP taxes, increased excise duties on various services and imported goods, and the introduction of a new minimum top-up tax for multinationals. The fragmented legislative approach, coupled with the timing of their passage (after the peak of the protests had subsided), undeniably contributed to the public perception of “secret” or circumvented legislative action. The government effectively achieved a significant portion of its fiscal objectives, albeit through a different, less consolidated legislative pathway, and by making strategic concessions on the most publicly visible and broadly unpopular taxes.

This episode vividly illustrates a complex and dynamic interplay between intense public pressure, strategic political maneuvering, and pressing fiscal imperatives within Kenya’s legislative process. It underscores the evolving power of citizen engagement, particularly the capacity of youth-led, social media-mobilized movements to effect immediate, tangible change, even if that change is subsequently recalibrated or partially circumvented through alternative legislative means. The government’s subsequent actions, including the introduction of a new online portal for public participation on the Finance Bill 2025, suggest an implicit acknowledgment of the urgent need for more transparent, genuinely inclusive, and responsive public engagement mechanisms to rebuild trust and avert future widespread unrest.

Recommendations

To foster a more robust and trustworthy legislative environment in Kenya, the following recommendations are put forth:

- Enhance Genuine and Transparent Public Participation: Beyond merely holding formal public forums, the government must ensure early, accessible, and meaningful public engagement platforms that demonstrably incorporate feedback into the drafting of bills, rather than just offering post-drafting review. The new online portal for Finance Bill 2025 is a positive step, but its ultimate effectiveness will depend on how public input is demonstrably integrated into the final legislation. Furthermore, investment in public education initiatives is crucial to demystify complex fiscal matters and legislative processes, fostering informed public debate and reducing susceptibility to misinformation.

- Promote Legislative Clarity and Consolidation: To foster trust and accountability, the government should avoid fragmenting major fiscal policy changes across multiple, less visible amendment bills. A single, comprehensive Finance Bill, with clear explanations of its provisions and their anticipated impact, would significantly enhance transparency and public oversight. Any subsequent amendments or new bills that reintroduce previously contentious measures must be clearly communicated, justified, and subjected to robust, well-publicized public scrutiny.

- Strengthen Accountability for State Violence: The government must prioritize and ensure accountability for security forces involved in the deaths, injuries, and abductions during the 2024 protests. Failure to address impunity for such actions perpetuates deep public resentment and undermines the rule of law.

- Re-evaluate Fiscal Strategy and Debt Management: Given the persistent public resistance to increased taxation on essential goods and services, the government should explore diversified revenue generation strategies. This includes intensified efforts to curb corruption, improve efficiency in existing tax collection mechanisms , and proactively engage in debt restructuring or renegotiation where feasible, to reduce reliance on measures that disproportionately burden ordinary citizens. A long-term fiscal strategy should explicitly consider the socio-economic impacts of tax policies on the cost of living, particularly for vulnerable populations, to ensure equitable burden-sharing and sustainable economic growth.

The Finance Bill 2024 remains a defining moment in Kenya’s political memory—proof that citizens hold power, but also a reminder that true reform requires vigilance long after the streets fall silent. As we reflect on what happened after the protests, one thing is clear: democracy only works when people stay informed, engaged, and unafraid to question the system. To continue digging into the broader shifts shaping governance across Africa, we recommend “Burkina Faso Dissolves Old Election Commission to Safeguard Sovereignty,” an insightful look into institutional restructuring in West Africa, and “Inside Chief Justice Koome’s Plan to Have Rigathi Gachagua Reinstated by August,” a revealing breakdown of internal power plays within Kenya’s judiciary.